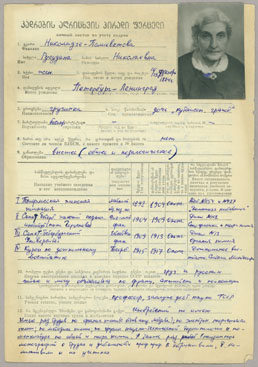

Rusudana Nikoladze-Polievktova, 1884-1942

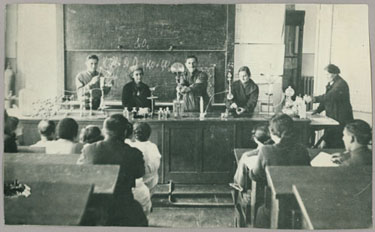

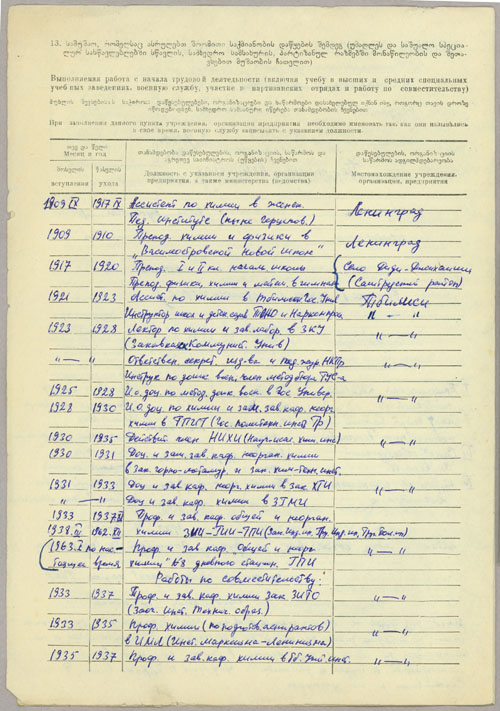

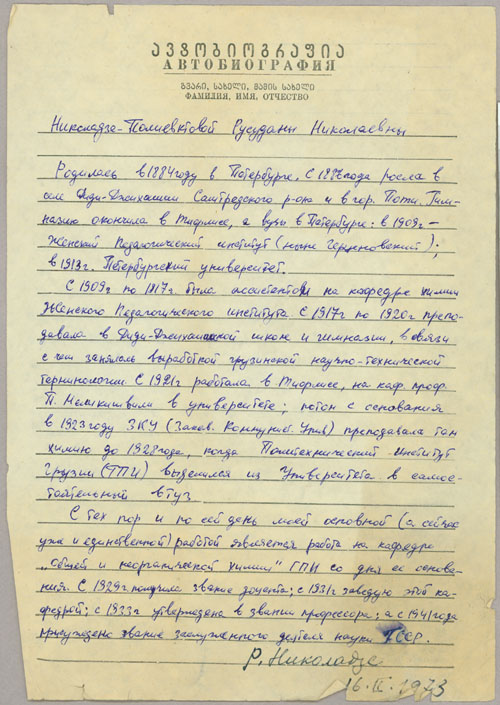

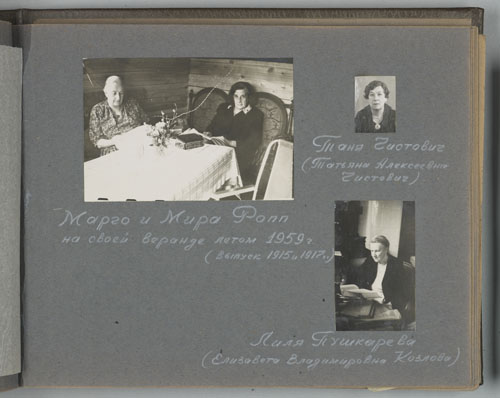

Rusudana Nikolaevna Nikoladze-Polievktova (1884-1981) was the oldest of three children of Niko Nikoladze. She was born in St. Petersburg but grew up in Georgia, moving between Poti, Tiflis (Tbilisi), and the family estate in the small western village of Didi-Dzhikhaishi. At her parent’s wishes she received a broad education. Rusudana graduated with specializations in mathematics and education from the Tiflis Gymnasium for Women in 1904 and matriculated at the Women’s Pedagogical Institute (WPI, now Herzen Pedagogical University) in St. Petersburg later that year. In 1900, 1903, and again in 1905 she traveled with her parents to Western Europe visiting England, Spain, France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. In the West she met many Russian revolutionary émigrés, including the anarchist Petr Kropotkin, “the father of Russian Marxism” George Plekhanov, and the young Bolshevik leader Lenin. In 1909 Rusudana received her degrees in physics and inorganic chemistry and began working as a junior researcher at WPI. Simultaneously, during the 1909-1910 school year she taught chemistry and physics at a St. Petersburg gymnasium, and attended St. Petersburg University from which she graduated in 1913 with a degree in organic chemistry. In addition to her native Georgian and equally impeccable Russian, Rusudana spoke English, French, and German. From 1915 to 1917 she also took higher pedagogical courses in preschool education, specializing in the new Montessori System. Her interest in education and its methods would continue throughout her life.

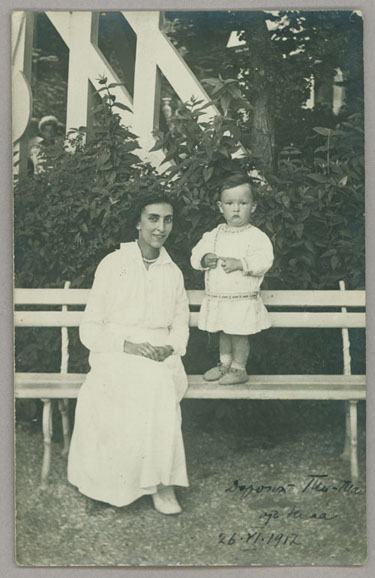

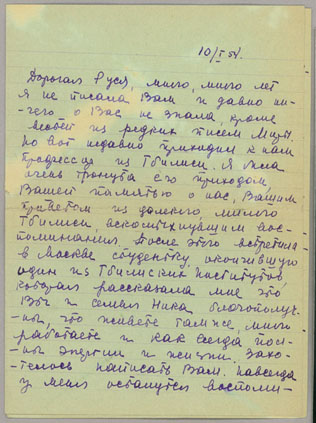

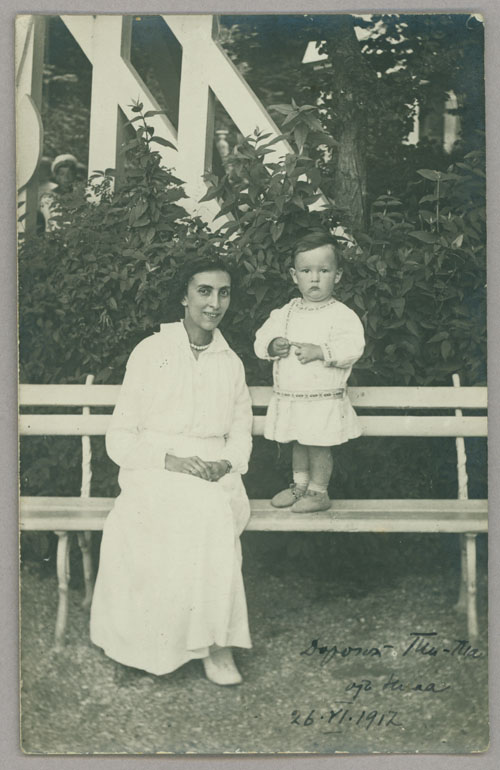

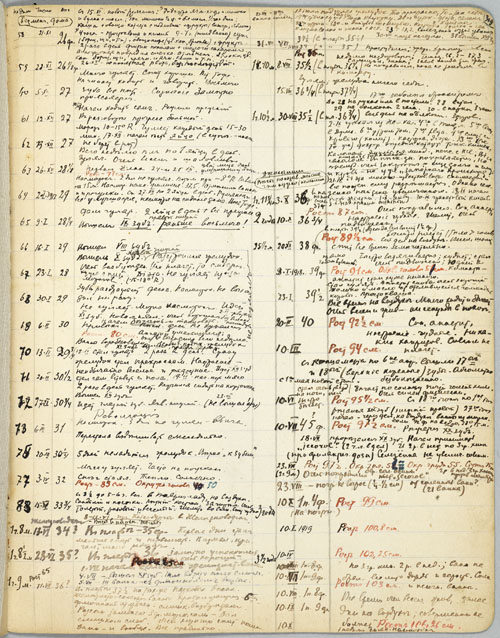

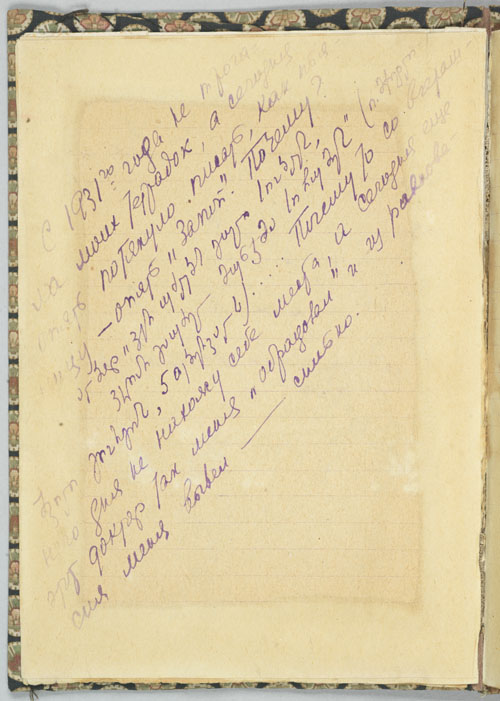

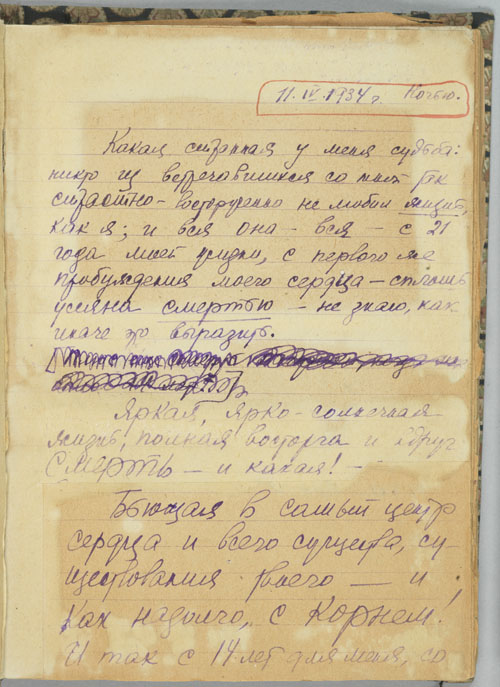

In the summer of 1913, Rusudana married the Petersburg historian Mikhail Aleksandrovich Polievktov. They were acquainted as early as 1907, when she was a senior at WPI and where he taught at the time. Their only child, Nikolai (Nika) Mikhailovich Nikoladze-Polievktov, was born in 1915. During 1913-1914 Rusudana accompanied her husband on several research trips to Berlin and Paris; they also visited Switzerland, France, and Scandinavia as tourists. The outbreak of the First World War caught the couple in Switzerland, penniless and unable to travel back to Russia across Central and Eastern Europe. They returned home only in late September 1914, after a long detour via Marseilles, Constantinople and Odessa. Rusudana recalled that on the last leg of the journey they were on the same boat with the members of the renowned K.S. Stanislavskii theater company. Her travels are described in great detail in her travelogues and diaries, which are now part of the Polievktov-Nikoladze Family Papers at Notre Dame.

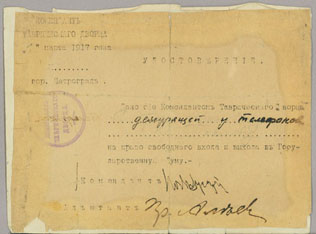

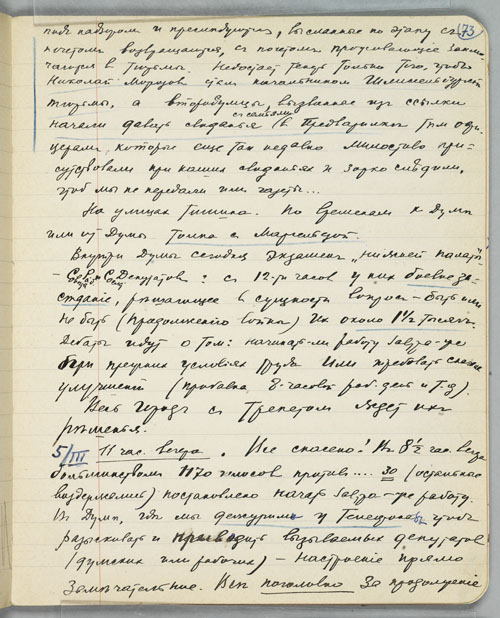

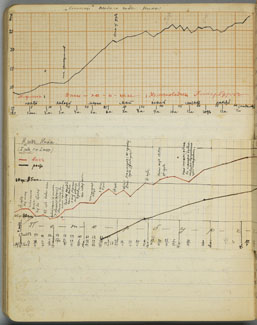

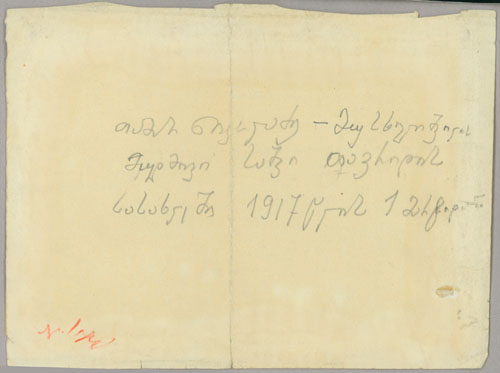

Considering the Left-leaning political orientation of the recently formed Polievktov-Nikoladze clan, it is hardly surprising that they greeted the news of the February Revolution with enthusiasm. Rusudana recorded in her diary that her parents’ reaction to the demise of the old order was even more jubilant and euphoric than her own or that of her younger sister Tamara (1892-1939), a recent graduate of the Women’s Pedagogical Institute. Within days, the Nikoladze sisters offered their services to the newly formed Petrograd Soviet and in the following weeks they worked eight-hour shifts every day inside the Tauride Palace as telephone operators on the lines designated for the Soviet’s leaders. (See Rusudana’s entry pass to the Duma exhibited). The sisters also played a major part in the work of the Interview (Polievktov) Commission. Rusudana’s careful, contemporaneous diary of her experiences during the February Revolution is also here on display.

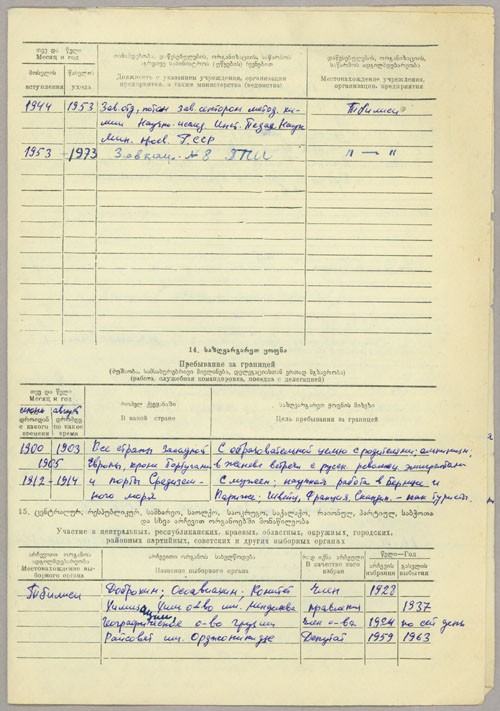

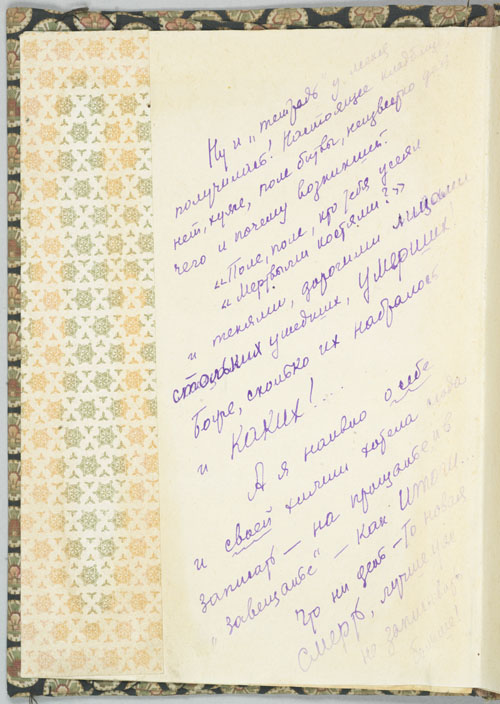

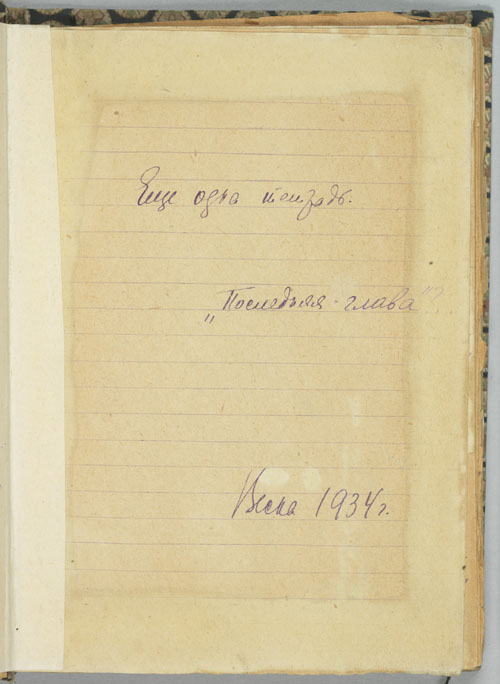

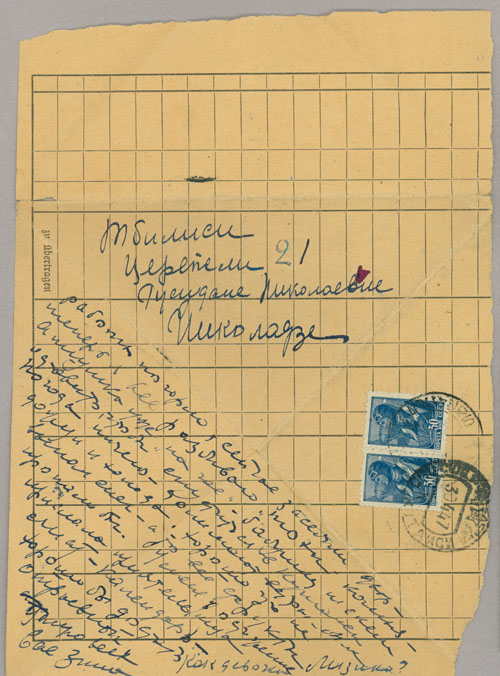

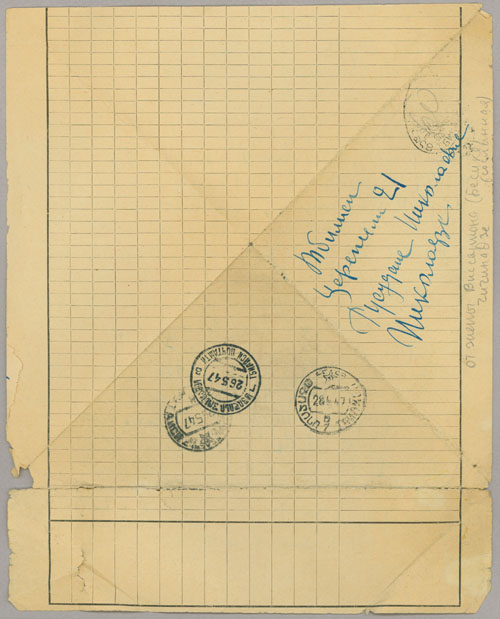

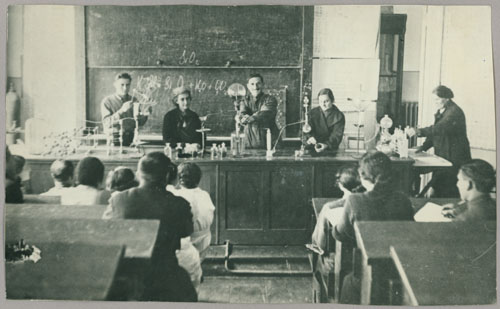

In July 1917, Rusudana and her toddler son returned to Didi-Dzhikhaishi, where she was among the founders of the local gymnasium and where she taught until 1920. She then moved to Tbilisi and until her retirement in the early 1970s worked at several institutions of higher education, beginning as a researcher and reaching, in 1933, the rank of Professor and Chair of the chemistry departments at Tbilisi State Pedagogical and Polytechnic Institutes. Rusudana was a prolific and talented writer, publishing scholarly works on organic and inorganic chemistry, chemistry methods, and Georgian chemistry terminology. She also completed two (unpublished) monographs on the life and works of famous Georgian chemists, Professors V. Petriashvili and P. Melikishvili, long (unpublished) memoirs on her St. Petersburg mentors, and accounts of her prerevolutionary life in both Georgian and Russian.

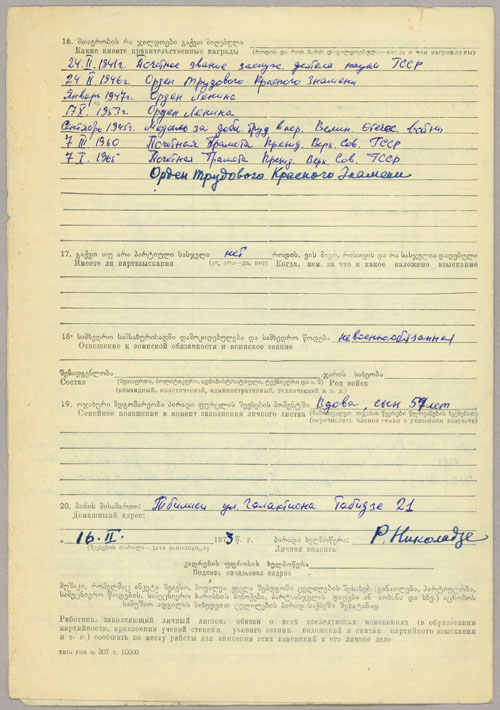

Though she was never a member of the Communist Party, Rusudana received numerous awards from the Soviet state, including the title of Honorary Scientist (1941), two Orders of Lenin (1947, 1953), the Order of the Red Banner (1965), and two Certificates of Merit from the Supreme Soviet of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (1960, 1965).

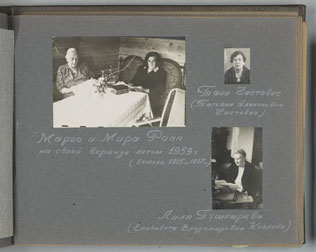

Rusudana’s son Nikolai became a prominent nuclear physicist and reportedly worked for the Soviet atomic bomb project under Kurchatov in the 1940s. He returned to Tbilisi around 1970 to be with his elderly mother and taught physics at the University. Rusudana’s father and younger siblings all passed away prior to the Second World War. After her husband’s death in 1942, she became the sole custodian of the family archive and dedicated her life to preserving their legacy and papers.

×