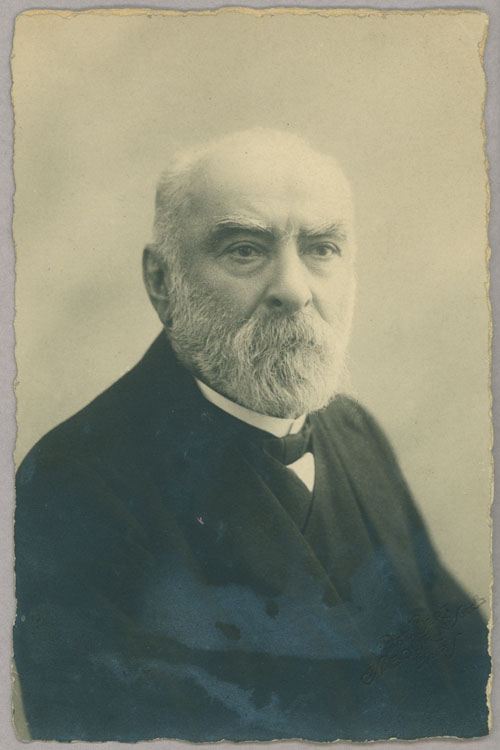

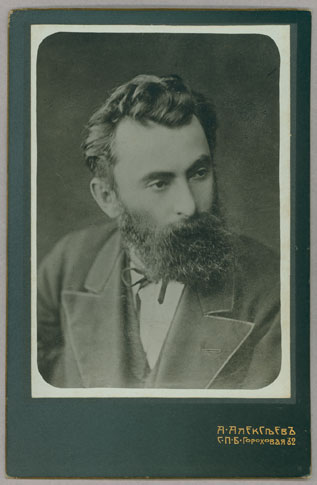

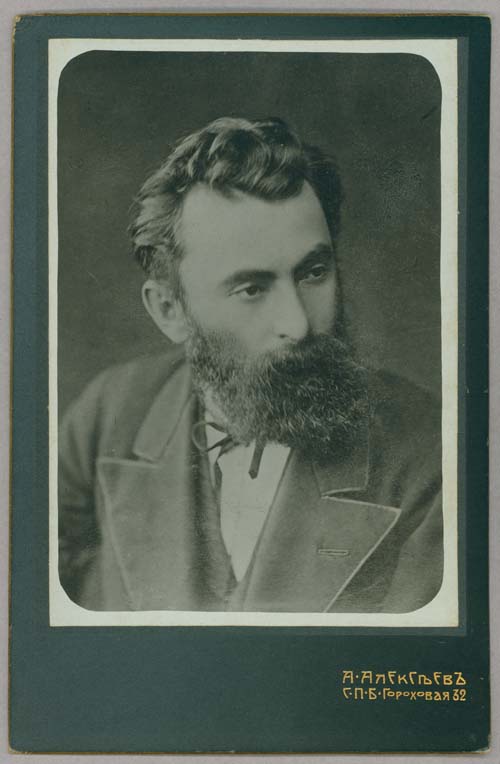

Niko Nikoladze, 1848-1928

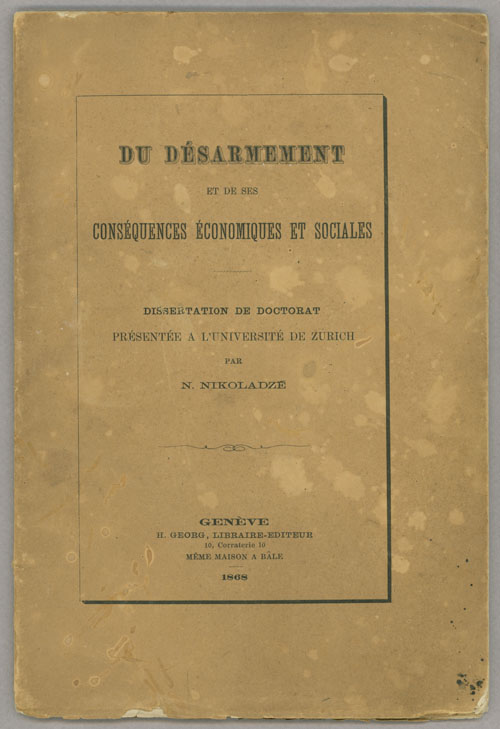

A leading Georgian revolutionary intellectual and public figure, Niko Nikoladze was born into an impoverished noble family in the western Georgia village of Didi-Dzhikhaishi. He graduated from Kutaisi Gymnasium in 1860 and enrolled the next year as a law student at St. Petersburg University. During his short stay in the imperial capital, Nikoladze was swayed by the populist ideas of Nikolai Chernyshevskii. After his expulsion from the University for involvement in student riots in 1861, Nikolazde moved to London where he collaborated with Alexander Herzen on Kolokol (Bell). Described by Herzen as “a tiger with milk flowing through his veins instead of blood,” Nikoladze advocated socialism in Georgia through the peasant commune. He later joined the international revolutionary community in Switzerland, and was acquainted with Léon Gambette, Karl Marx, and later, Léon Blum. Marx invited him to form a Caucasian delegation to the Workingmen’s International, but he rejected the offer because he was convinced that change would come through the village. In 1868 Nikoladze became the first Georgian ever to receive a doctorate from a European university. He defended his dissertation on disarmament in Europe (exhibited here) at the University of Zurich.

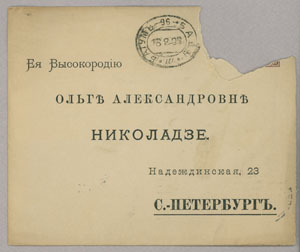

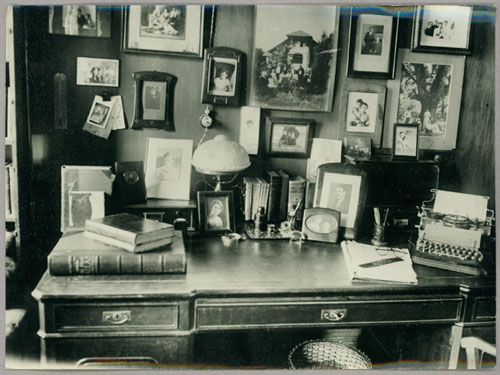

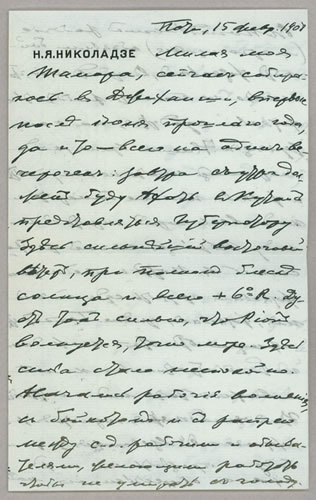

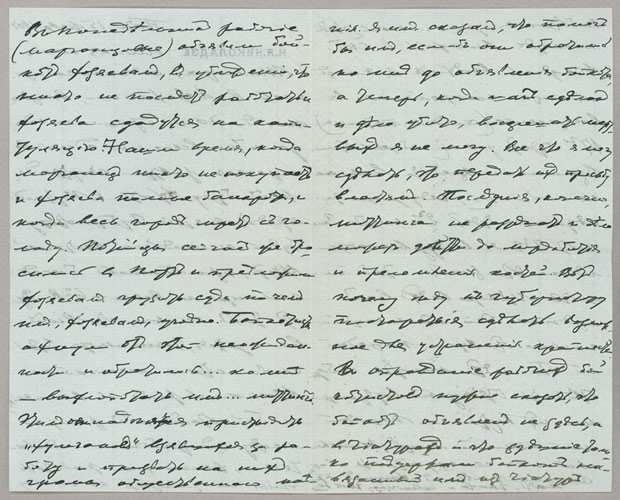

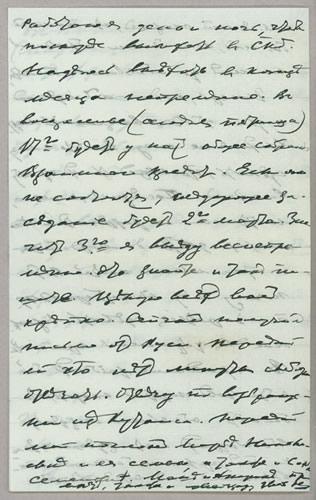

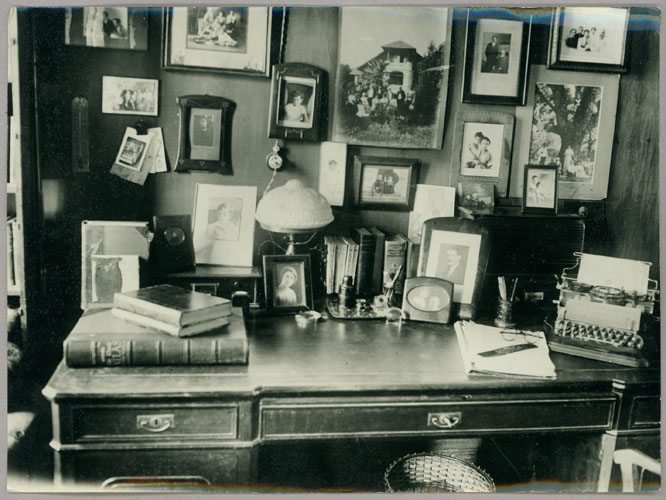

After his return to Russia in 1875, Nikoladze abandoned the radicalism of his youth and instead focused his boundless energy on promoting more gradual changes. He saw economic growth and trade, rather than revolutionary propaganda or the Georgian language, as the sine qua non to national survival. He was an advocate of self-government rather than independence and emphasized practical work and cooperation with the Russian liberal intelligentsia. By the 1890s, Nikoladze had settled for an evolutionary path to socialism, promoted by cooperatives, mutual credit societies, and technology. He rejected the class struggle and became increasingly patriotic. From 1894 to 1913 he served as elected Mayor of Poti on Georgia’s Black Sea coast and by end of his term transformed the city into a major seaport. Between 1913 and 1917 Nikoladze lived in Petersburg/Petrograd with his wife Olga Aleksandrovna née Guramishvili and their younger daughter Tamara. His older daughter Rusudana, her husband the historian Mikhail Aleksandrovich Polievktov and their son Nika lived in the same building.

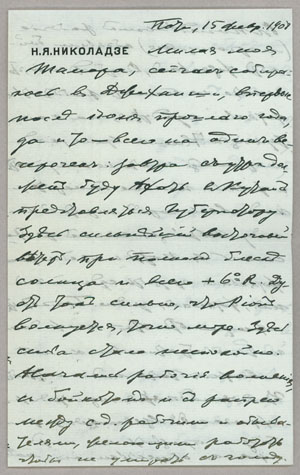

Throughout his life, Nikoladze was a prolific writer and a noted publicist. He founded, edited or was on the editorial board of many different publications—including the venerated Russian populist monthly Otechestvennye zapiski (Notes on Fatherland) and the influential Petrograd patriotic daily Russkaia volia (Russia’s Freedom).

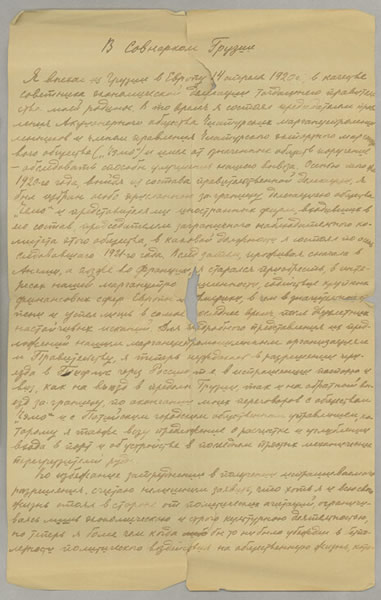

In June 1917 Nikoladze returned to Georgia and joined the liberal National Democratic Party. Following the Bolshevik takeover in October, he supported Georgia’s independence from Soviet Russia. But instead of mounting political opposition to the new regime he again focused his energies on bringing change through technical and economic progress. For the most part of the next decade he lived in England and France trying to attract foreign investment, especially for the development of Georgia’s untapped manganese resources. He spent the last year of his life in Tbilisi working on a monumental project aimed at transforming the vast Kolkhida swamps into arable land. He died in his home on June 5, 1928 and was buried in the Old Tbilisi Pantheon for famous national writers and public figures.

Selected Bibliography

Jones, Stephen F., Socialism in Georgian Colors: The European Road to Social Democracy, 1883-1917 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005).

Suny, Ronald G., The Making on the Georgian Nation (Bloomington: Indiana University Press in association with Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, Stanford, Calif., 1988).