The Society for the Study of Revolution and the Interview (Polievktov) Commission of the Tauride Palace

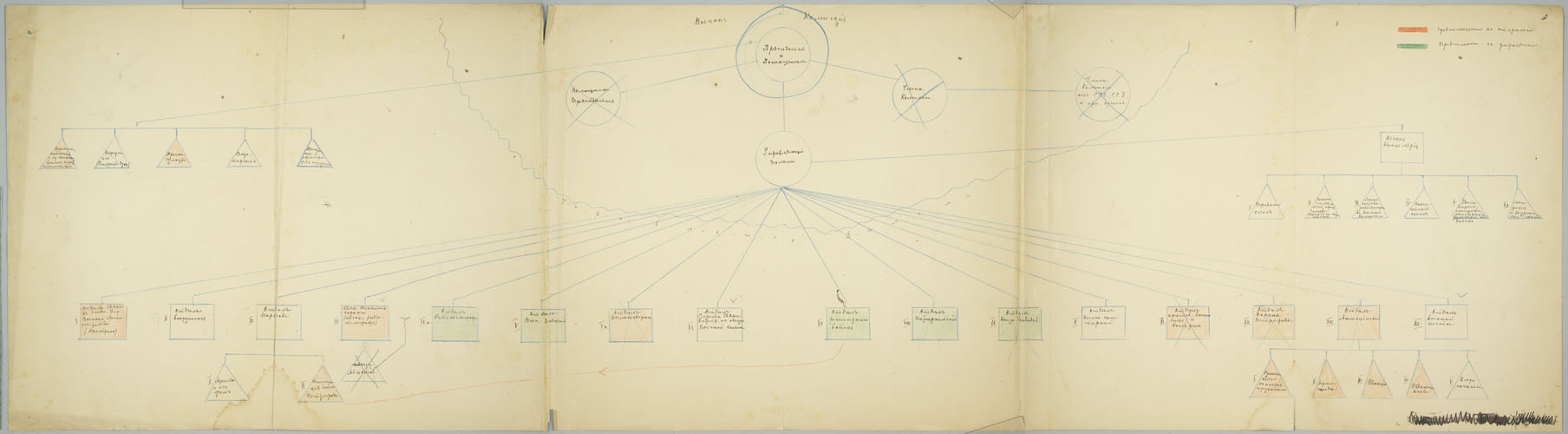

In early March, 1917, M.A. Polievktov and his friend and fellow historian A.E. Presniakov launched an effort to collect materials on the historic events of the February Revolution; by April, the new Society for the Study of the [Russian] Revolution (SSR) was formed and officially recognized. The SSR sent out an official announcement urging citizens of the new Russia to collect any materials pertaining to the history of the February Revolution—from official documents, memoirs, notes, diaries and personal accounts to books, leaflets, songs and verses, drawings and photographs, advertisements, and records of meetings by political and social organizations—and send them to the SSR. It was also decided to divide the SSR into several sections, each collecting materials documenting the contribution of a particular group to the overthrow of the old regime. The section called the Interview Commission of the Tauride Palace, headed by Polievktov, set out “to interview those participants of the [February] coup who were active during the revolutionary days inside the Tauride Palace or were involved in forming the Temporary Committee of the State Duma, the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, and the other entities organized there” (from the Letter of Introduction by Presniakov).

Exactly how many people responded to this appeal remains unknown, but in the end the Interview or Polievktov Commission produced transcripts of thirteen complete interviews and half a dozen brief summaries of conversations with active participants of the February Days, including Nikolai Nikolaevich Krasnov , Stepan Vasil’evich Sufshchinskii, Aleksandr Fedorovich Kerenskii, and Matvei Ivanovich Skobelev.

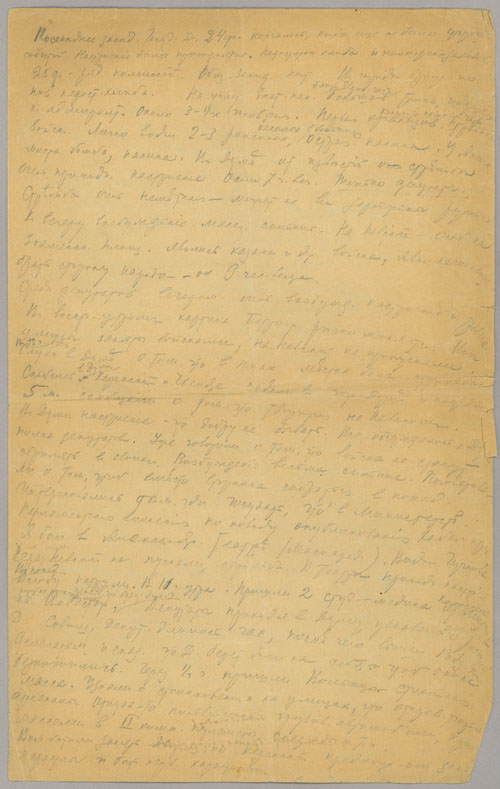

May 1917 was the Commission’s most productive period; all but one interview was conducted during that month. The interview sessions lasted anywhere from one to several hours and, with only two exceptions, took place either in the Tauride Palace or in government offices. The length of the interviews, which varied greatly, seemed to depend more on the interviewee’s readiness to talk than on the prominence of his position. Some were recorded over the course of two or more sessions. Each interviewee was asked about his participation in the revolutionary events of February 25–March 3, 1917, that is, from the outbreak of the popular uprising in Petrograd to the formation of the Provisional Government and the abdications of Nicholas II and Grand Duke Michael. Following this initial testimony, the interviewers posed more pointed questions. Though the specific questions were suppressed from the available transcripts, they could be surmised from the interviewees’ answers. Recurring among these were queries on the soldiers’ uprising; conspiracies against Nicholas II; the arrests and initial custody of the most notorious of tsarist ministers and other police, military and government officials; the formation of the Petrograd Soviet and the Provisional Government; the origins of dual power and of Order Number One; and the abdications. As May 1917 witnessed the break up of the first revolutionary government and formation of the first coalition cabinet, some of the more politically involved interviewees were also asked about the events leading up to the most recent crisis, including Miliukov’s diplomatic note to the Allies and the April demonstrations in Petrograd. By and large, however, the interviews remained focused on the February Days, and as far as we can determine, the interviewees were not intentionally drawn into making normative evaluations.

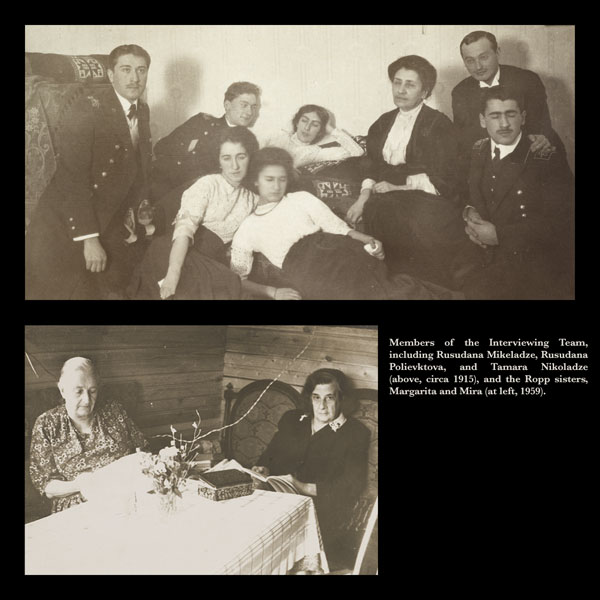

Each interview was conducted by three or four members of the Interview Commission, one leading the conversation and everyone taking minutes. All transcripts were then read and compared, corrected, and transcribed into an aggregate master version. This, depending on the circumstances of the moment, would normally be accomplished on the day of the interview or shortly thereafter. The master versions would then be turned over to Polievktov for a final editing that—as far as we can establish—focused on matters of presentation and consistency, not historical accuracy. Polievktov did the bulk of the editing in fairly short order, not long after master versions were prepared by his assistants and handed over to him, and certainly no later than September 1917.

Convincing former participants, many of whom continued to be politically active under the transitional regime, to sit down for an interview session was no easy task. Rusudana Polievktova-Nikoladze recalled that those on the Left were far less cooperative (many simply refused to be interviewed) than their more moderate colleagues. Chkheidze, for example, demanded the questions in advance, had to be chased after, and in general proved difficult to accommodate. Kerenskii, on the other hand, was noted by the memoirist to be the only representative of the Left genuinely excited about the project. He brought the interviewing team to his office in his ministerial automobile and was quite expansive in his deposition. Skobelev, too, was cooperative and forthcoming, even talkative, though his willingness to be interviewed was probably a result of personal connections with the Nikoladze sisters, in particular with their cousin Kaki Tsereteli. In fact, Tsereteli was present during part of Skobelev’s three-session long interview and even inserted a qualifying remark concerning the origins of dual power.

Whatever their initial hesitation, almost all loosened up and began talking as soon as they sat down for the actual interview. It is important to note that only four of the twelve interviewees later wrote memoirs or left behind additional testimonies, but these proved to be far less revealing than their May 1917 interviews. For the rest of the interviewees, these depositions would become their only recorded testimonies.

The Society for the Study of the [Russian] Revolution Questionnaire. 1917

This questionnaire is a late example of the form used by the Society for the Study of the Revolution (SSR)

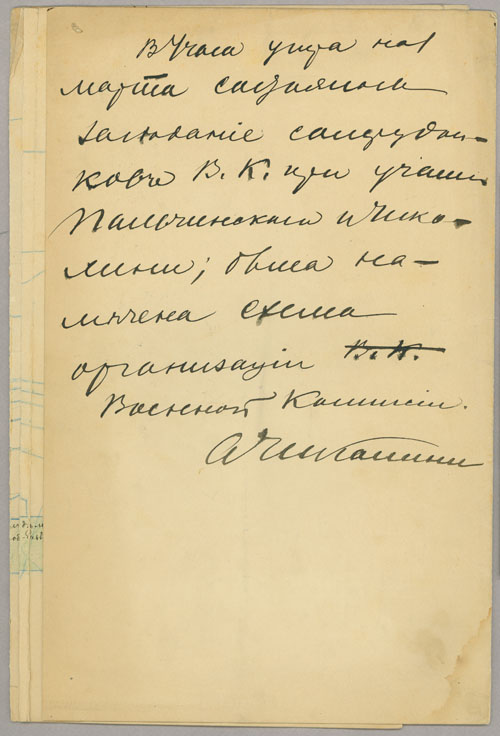

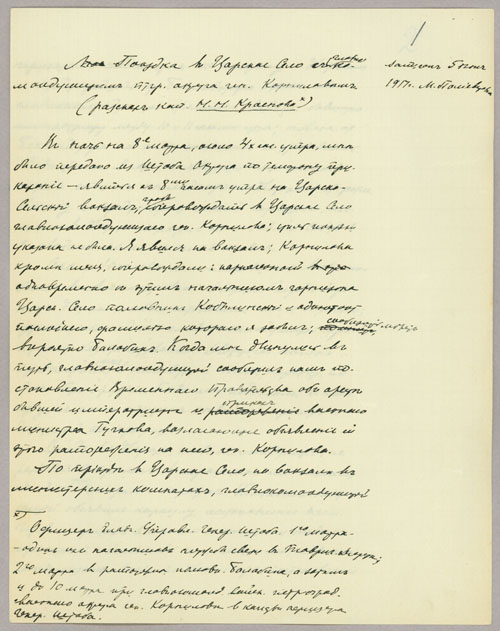

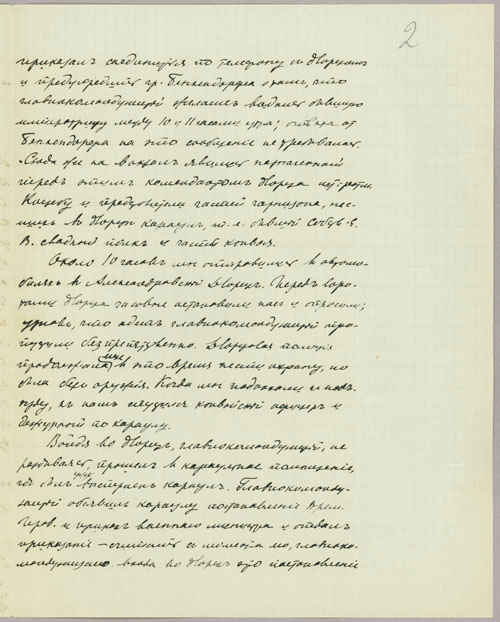

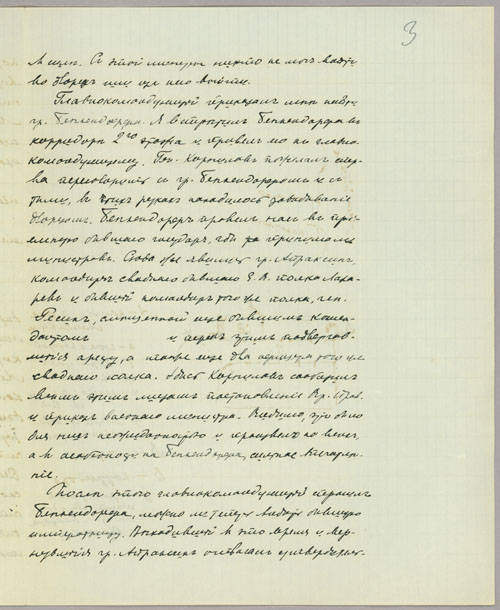

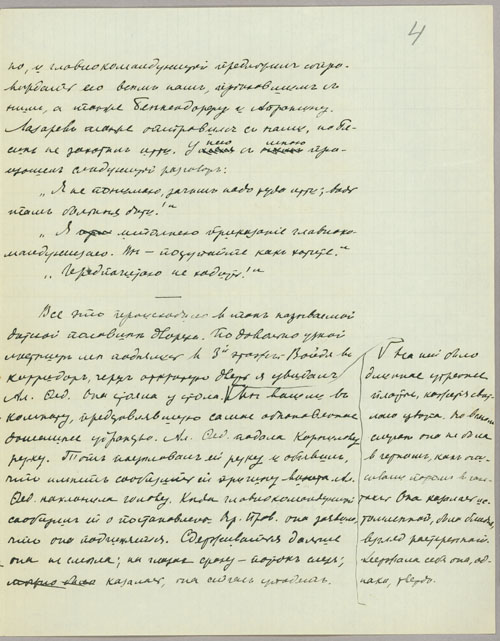

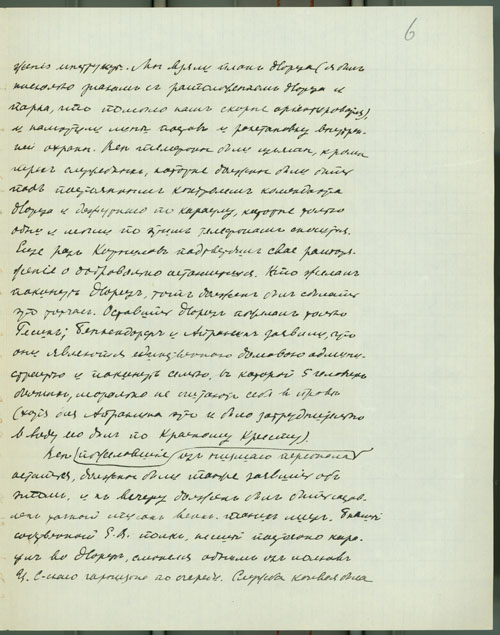

The Arrest of the Tsarina Aleksandra Fedorovna Romanov, March 8, 1917—as recounted by Captain N.N. Krasnov.

During March 2-10, 1917 General Staff Captain Nikolai Nikolaevich Krasnov served as an orderly under the first revolutionary Commander-in-Chief of the Petrograd Military District, General L. G. Kornilov. On March 8, Krasnov accompanied Kornikov to Tsarskoe Selo, the favorite residence of Nicholas II and his family, to arrest the former empress Aleksandra Fedorovna

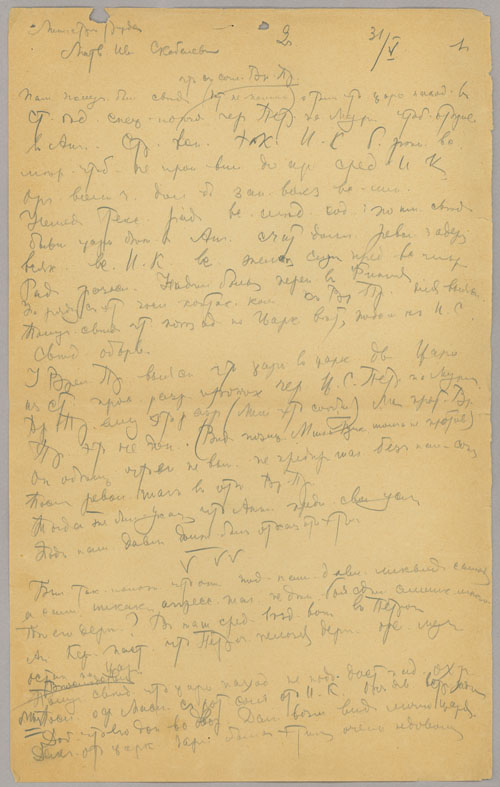

An excerpt from the interview with A.F. Kerenskii as recorded on May 31, 1917 by Tamara Nikoladze. The interview represents Kerenskii’s earliest, most expansive, and most reliable testimony on the February Revolution.

An excerpt from the interview with M. I. Skobelev, as recorded on May 31, 1917”