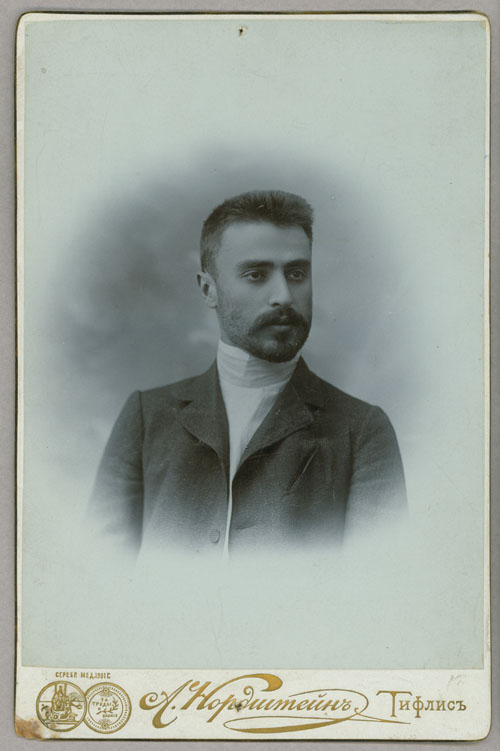

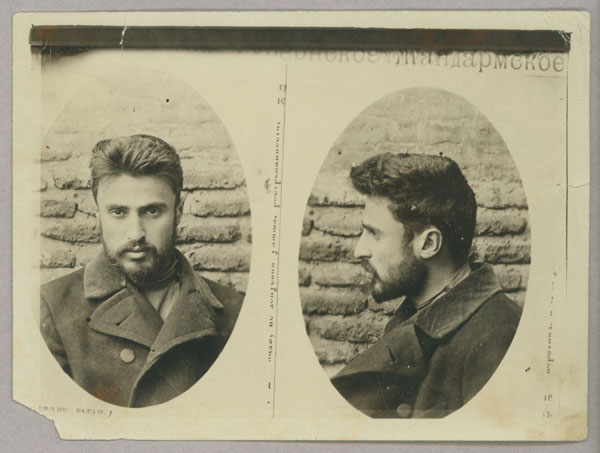

Irakli Tsereteli, 1881-1959

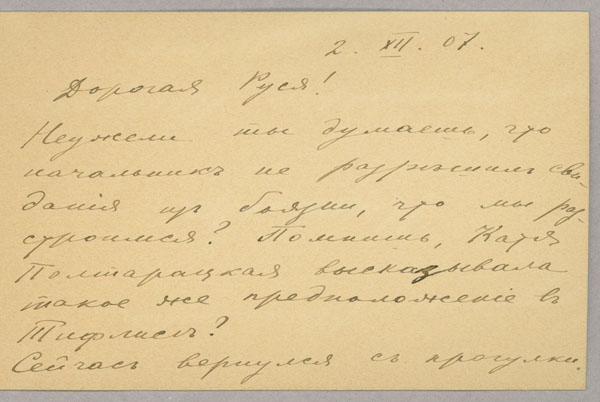

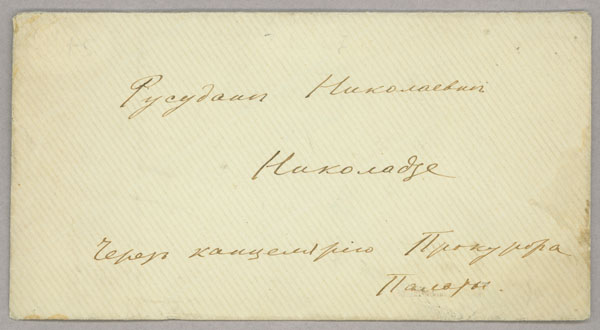

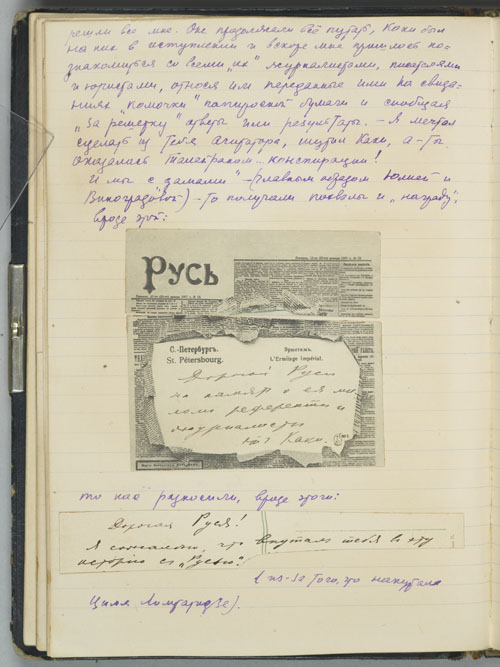

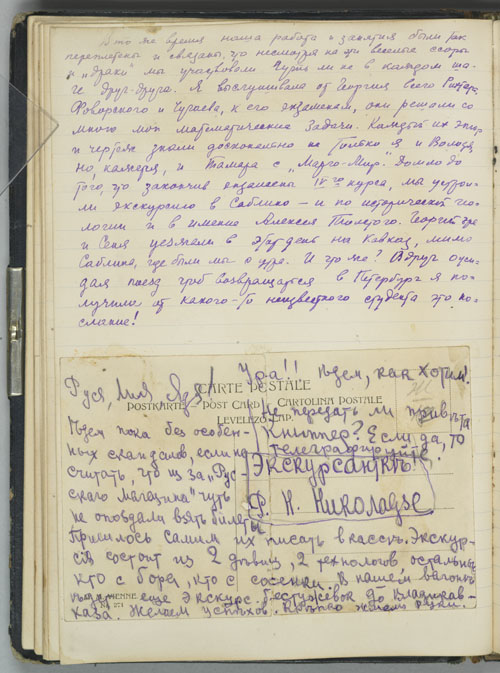

Rusudana Nikoladze. Scrapbook, 1907.

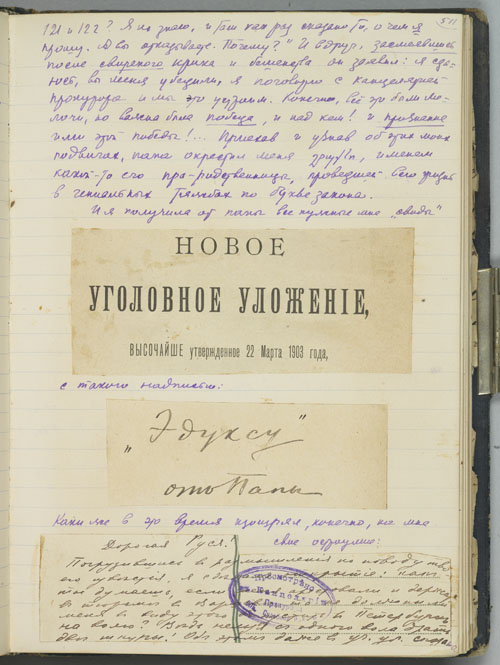

When the tsarist government dissolved the Second Duma on June 3, 1907, Tsereteli and his fellow Social Democratic deputies were arrested and accused of high treason. Tsereteli’s cousin, Rusudana Nikoladze, then a student at the Women’s Higher Pedagogical Institute, regularly visited him in prison. During one such visit she smuggled out Tsereteli’s notes on his experiences in the Duma, which were soon published by the exiled Menshevik leader Iu. O. Martov in Geneva (Ternii bez roz, Geneva, 1908). She also served as a go-between for the imprisoned Duma deputies and their defense attorney, Nikolai Dmitrievich Sokolov, himself a prominent Petrograd Social Democrat. Rusudana’s scrapbook contains numerous postcards from Irakli (called “Kaki” in the family) in prison. In the accompanying excerpt Rusudana describes her activities for Kaki Tsereteli and his comrades during that time.

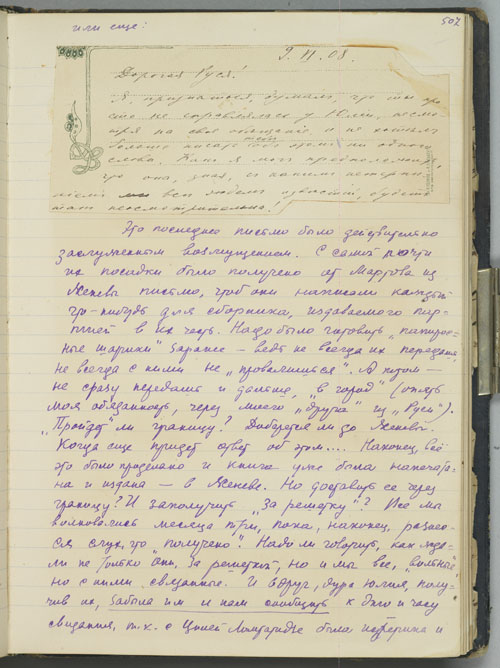

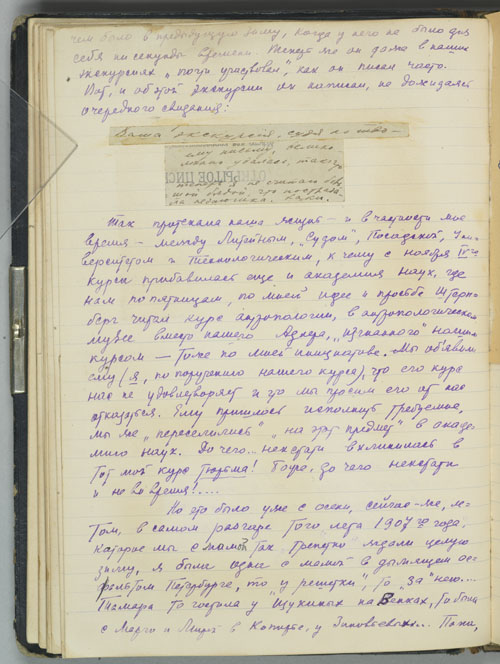

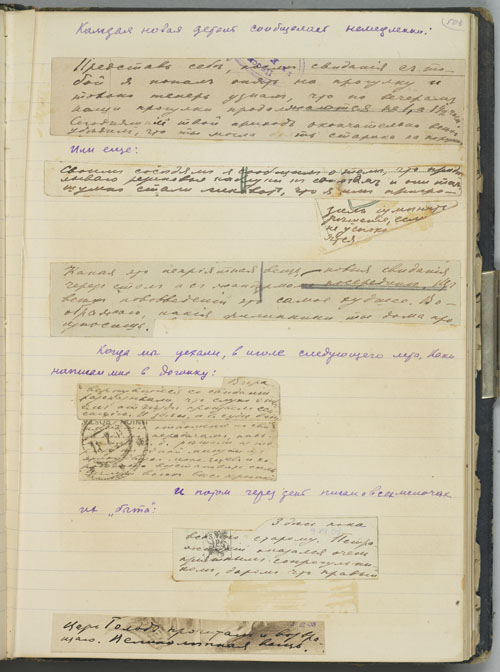

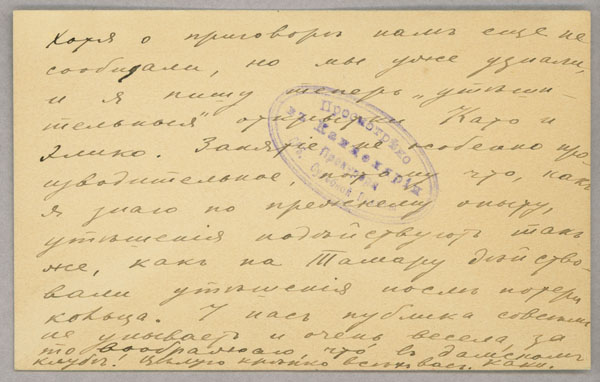

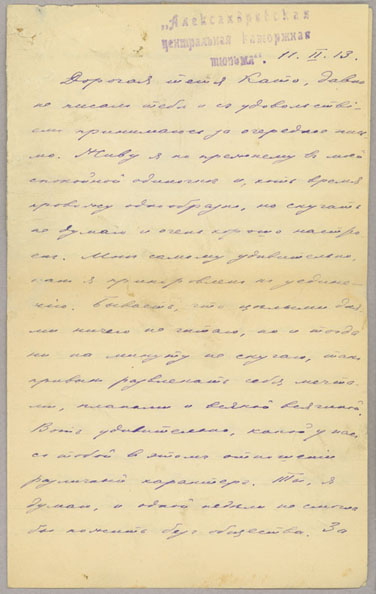

Letter from Irakli Tsereteli in Aleksandrovskii Prison, Irkutsk, to E. L. Nikoladze (Kato) in Kutaisi, February 11, 1913.

By the time this letter was written Tsereteli had spent more than four years in prison, in St. Petersburg, Nikolaev, and Irkutsk. The stamp at the upper right reads “Aleksandrovskii Central Prison for Penal Servitude”; on the opposing page is the censor’s mark.

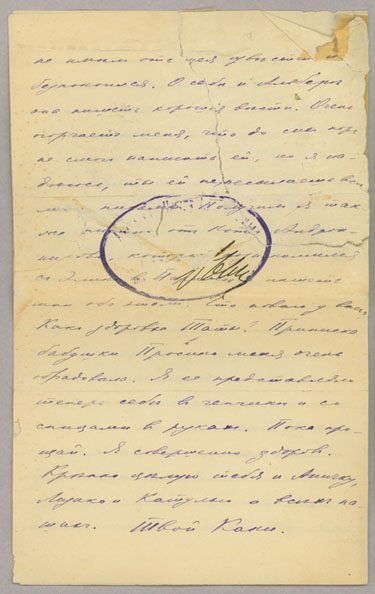

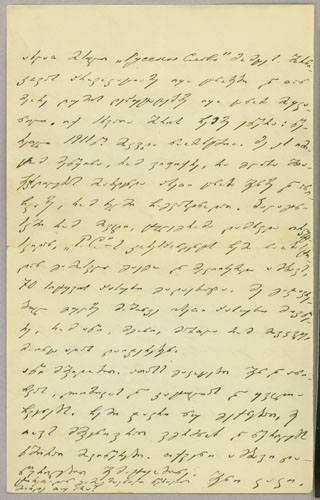

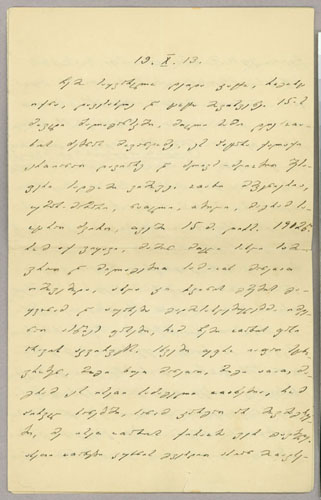

Letter from Irakli Tsereteli in Usol’e to E. L. Nikoladze (Kato) in Kutaisi, October 19, 1913.

In the fall of 1913, Tsereteli joined many other political exiles in the small Siberian village of Usol’e located on the Trans-Siberian Railway. The Polievktov-Nikoladze Collection contains dozens of Tsereteli’s letters from Siberian exile to his family, written both in Russian and in Georgian.

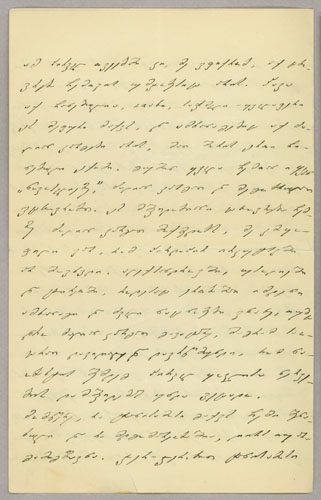

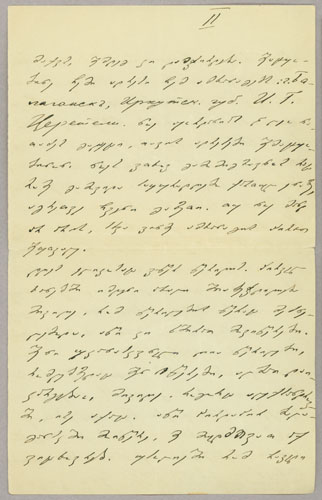

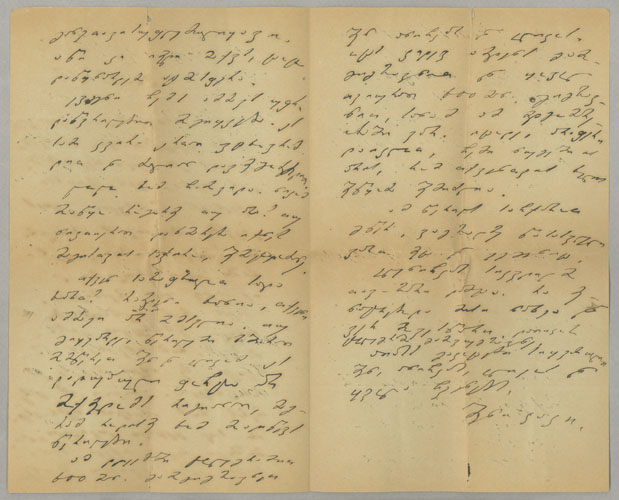

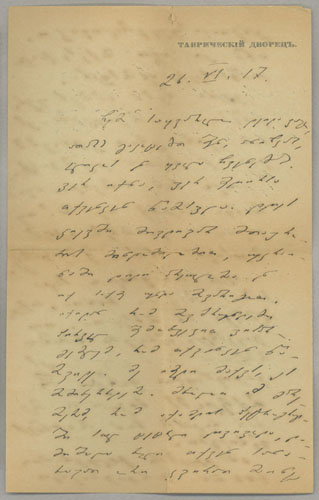

Letter from Irakli Tsereteli in Petrograd to E. L. Nikoladze (Kato) in Kutaisi, June 26, 1917.

On June 26, 1917, Tsereteli wrote this letter, in Georgian, to his aunt Kato Nikoladze on the stationary of the Tauride Palace, which was the official seat of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. Tsereteli writes that he is on his way to the train station to travel to Kiev as part of a three-member delegation (the others were Kerensky and Tereshchenko) of the Provisional Government, in an attempt to dissuade the Ukrainian Central Rada from declaring national and territorial autonomy from Russia. He also tells his aunt that he will try to visit her and her sister Anna soon after his return from Kiev and that he will wire them money by telegraph, 600 rubles monthly.

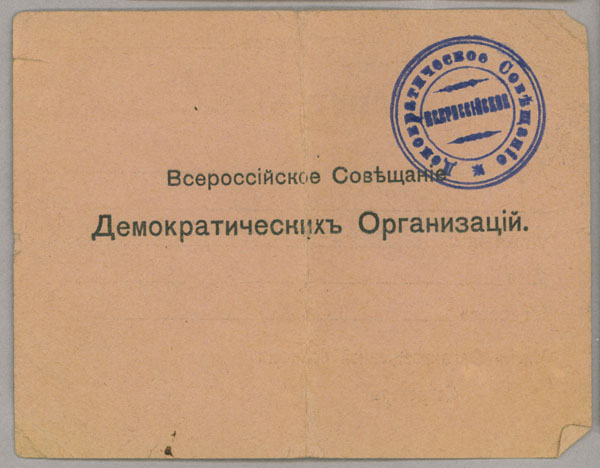

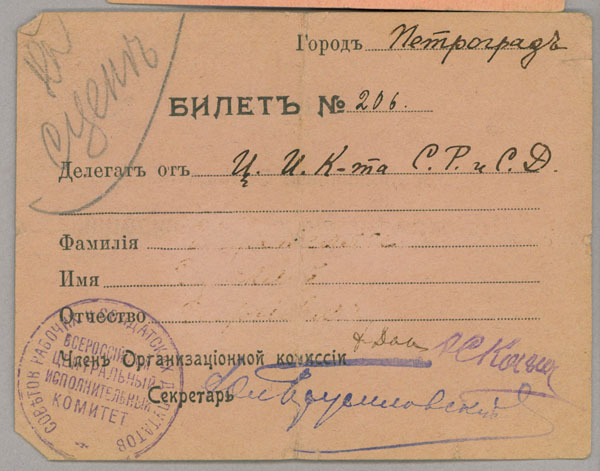

Pass (No. 206) for a seat on the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee, September, 1917

This is Tsereteli’s pass for a seat on the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee, to participate in the All-Russian Conference of Democratic Organizations in September, 1917.

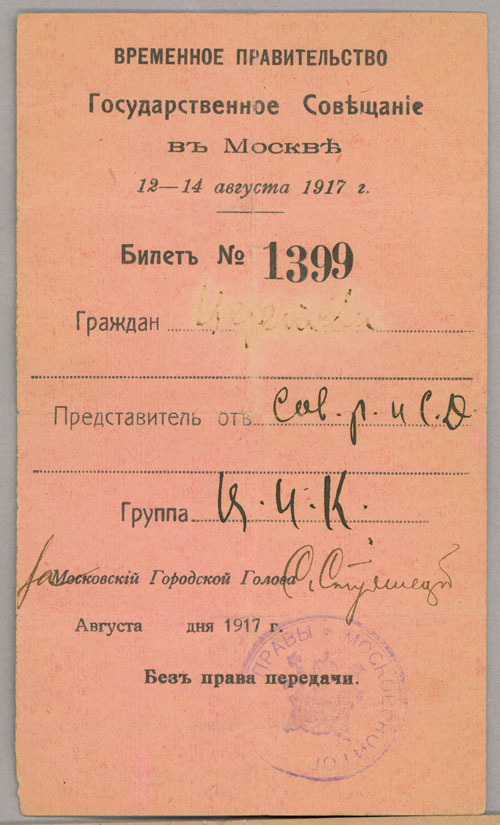

Pass (No. 1399) to the State Conference in Moscow, August 12-14, 1917.

This is Tsereteli’s Provisional Government pass to the State Conference in Moscow as a representative of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Soldiers’ and Workers’ Deputies. Although his name can still be read, someone—probably his cousin Rusudana who was the custodian of the family documents throughout most of the Soviet period—has tried to erase it, as incriminating evidence of the family’s connection with the February bourgeois revolution.

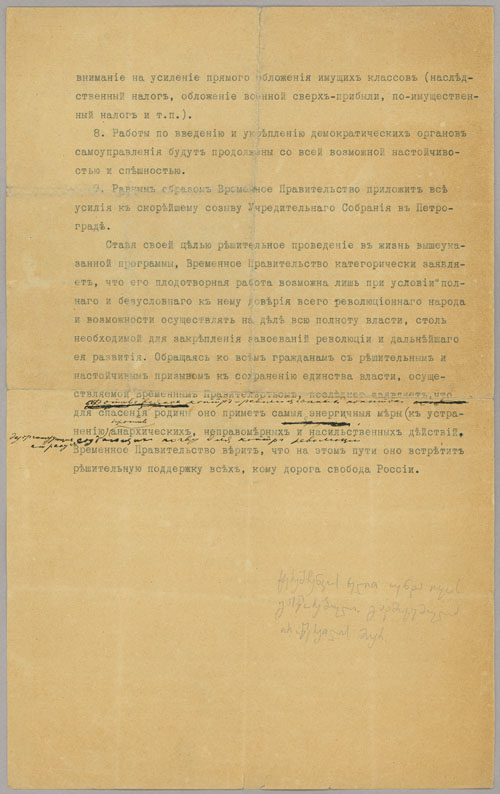

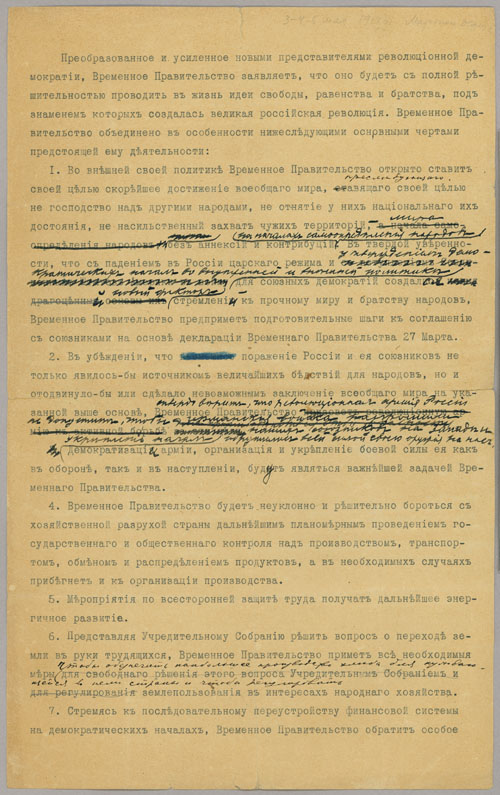

Tsereteli’s draft Declaration of the first coalition cabinet of the Provisional Government, May 5, 1917.

This is a draft of the Declaration (program) of the coalition government, including Tsereteli’s suggested changes, in his hand. All Tsereteli’s changes were adopted in the final Declaration, which was published in the official bulletin of the Provisional Government on May 6, 1917. The Declaration was signed by Prince G. E. L’vov, Minister-President, and all other ministers.

For English translation, please consult:

Browder, Robert P., ed., The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961): 1276-1277.